Quote of the Day

Part VI of excerpts from the chapter entitled “The Road to Nowhere” from David Horowitz’s The Politics of Bad Faith. Another long one:

By 1917, Russia was already the 4th industrial power in the world. Its rail networks had tripled since 1890, and its industrial output had increased by three-quarters since the century began. Over half of all Russian children between eight and eleven years of age were enrolled in schools, while 68% of all military conscripts had been tested literate. A cultural renaissance was underway in dance, painting, literature and music, the names Blok, Kandinsky, Mayakovsky, Pasternak, Diaghelev, Stravinsky were already figures of world renown. In 1905 a constitutional monarchy with an elected parliament had been created, in which freedom of the press, assembly and association were guaranteed, if not always observed. By 1917, legislation to create a welfare state, including the right to strike and provisions for workers’ insurance was already in force and — before it was dissolved by Lenin’s Bolsheviks — Russia’s first truly democratic democratic parliament had been convened.

The Marxist Revolution destroyed all this, tearing the Russian people out of history’s womb and robbing whole generations of their minimal birthright, the opportunity to struggle for a decent life. Yet even as this political abortion was being completed and the nation was plunging into its deepest abyss, the very logic of revolution forced its leaders to expand their Lie: to insist that the very nightmare they had created was indeed the kingdom of freedom and justice the revolution had promised.

It is in this bottomless chasm between reality and promise that our own argument is finally joined. You seek to separate the terror-filled actualities of the Soviet experience from the magnificent harmonies of the socialist dream. But it is the dream itself that begets the reality, and requires the terror. This is the revolutionary paradox you want to ignore.

Isaac Deutscher had actually appreciated this revolutionary equation, but without ever comprehending its terrible finality. The second volume of his biography of Trotsky opens with a chapter he called “The Power and The Dream.” In it, he described how the Bolsheviks confronted the situation they had created: “When victory was theirs at last, they found that revolutionary Russia had overreached herself and was hurled down to the bottom of a horrible pit.” Seeing that the revolution had only increased their misery, the Russian people began asking: “Is this…the realm of freedom? Is this where the great leap has taken us?” The leaders of the Revolution could not answer. “[While] they at first sought merely to conceal the chasm between dream and reality [they] soon insisted that the realm of freedom had already been reached — and that it lay there at the bottom of the pit. ‘If people refused to believe, they had to be made to believe by force.’ “

So long as the revolutionaries continued to rule, they could not admit that they had made a mistake. Though they had cast an entire nation into a living hell, they had to maintain the liberating truth of the socialist idea. And because the idea was no longer believable, they had to make the people believe by force. It was the socialist idea that created the terror.

Because of the nature of its political mission, this terror was immeasurably greater than the repression it replaced. Whereas the Czarist police had several hundred agents at its height; the Bolshevik Cheka began its career with several hundred thousand. Whereas the Czarist secret police had operated within the framework of a rule of law, the Cheka (and its successors) did not. The Czarist police repressed extra-legal opponents of the political regime. To create the socialist future, the Cheka targeted whole social categories — regardless of individual behavior or attitude — for liquidation.

The results were predictable. “Up until 1905,” wrote Aleksander Solzhenitsyn, in his monumental record of the Soviet gulag, “the death penalty was an exceptional measure in Russia.” From 1876 to 1904, 486 people were executed or seventeen people a year for the whole country (a figure which included the executions of non-political criminals). During the years of the 1905 revolution and its suppression, “the number of executions rocketed upward, astounding Russian imaginations, calling forth tears from Tolstoy and…many others; from 1905 through 1908 about 2,200 persons were executed—forty-five a month. This, as Tagantsev said, was an epidemic of executions. It came to an abrupt end.”

But then came the Bolshevik seizure of power: “In a period of sixteen months (June 1918 to October 1919) more than sixteen thousand persons were shot, which is to say more than one thousand a month.” These executions, carried out by the Cheka without trial and by revolutionary tribunals without due process, were executions of people exclusively accused of political crimes. And this was only a drop in the sea of executions to come. The true figures will never be known, but in the two years 1937 and 1938, according to the executioners themselves, half a million ‘political prisoners’ were shot, or 20,000 a month.

To measure these deaths on an historical scale, Solzhenitsyn also compared them to the horrors of the Spanish Inquisition, which during the 80 year peak of its existence, condemned an average of 10 heretics a month. The difference was this: The Inquisition only forced unbelievers to believe in a world unseen; Socialism demanded that they believe in the very Lie that the revolution had condemned them to live.

I am reminded here again of Eric Hoffer’s observation to Eric Sevareid during an interview:

I have no grievance against intellectuals. All that I know about them is what I read in history books and what I’ve observed in our time. I’m convinced that the intellectuals as a type, as a group, are more corrupted by power than any other human type. It’s disconcerting to realize that businessmen, generals, soldiers, men of action are less corrupted by power than intellectuals.

In my new book I elaborate on this and I offer an explanation why. You take a conventional man of action, and he’s satisfied if you obey, eh? But not the intellectual. He doesn’t want you just to obey. He wants you to get down on your knees and praise the one who makes you love what you hate and hate what you love. In other words, whenever the intellectuals are in power, there’s soul-raping going on.

Continuing:

The author of our century’s tragedy is not Stalin, nor even Lenin. Its author is the political Left that we belonged to, that was launched at the time of Gracchus Babeuf and the Conspiracy of the Equals, and that has continued its assault on bourgeois order ever since. The reign of socialist terror is the responsibility of all those who have promoted the Socialist idea, which required so much blood to implement, and then did not work in the end.

But if socialism was a mistake, it was never merely innocent in the sense that its consequences could not have been foreseen. From the very beginning, before the first drop of blood had ever been spilled, the critics of socialism had warned that it would end in tyranny and that economically it would not work. In 1844, Marx’s collaborator Arnold Ruge warned that Marx’s dream would result in “a police and slave state.” And in 1872, Marx’s arch rival in the First International, the anarchist Bakunin, described with penetrating acumen the political life of the future that Marx had in mind:

This government will not content itself with administering and governing the masses politically, as all governments do today. It will also administer the masses economically, concentrating in the hands of the State the production and division of wealth, the cultivation of land,…All that will demand…the reign of scientific intelligence, the most aristocratic, despotic, arrogant, and elitist of all regimes. There will be a new class, a new hierarchy…the world will be divided into a minority ruling in the name of knowledge, and an immense ignorant majority. And then, woe unto the mass of ignorant ones!

If a leading voice in Marx’s own International could see with such clarity the oppressive implications of his revolutionary idea, there was no excuse for the generations of Marxists who promoted the idea even after it had been put into practice and the blood began to flow. But the idea was so seductive that even Marxists who opposed Soviet Communism, continued to support it, saying this was not the actual socialism that Marx had in mind, even though Bakunin had seen that it was.

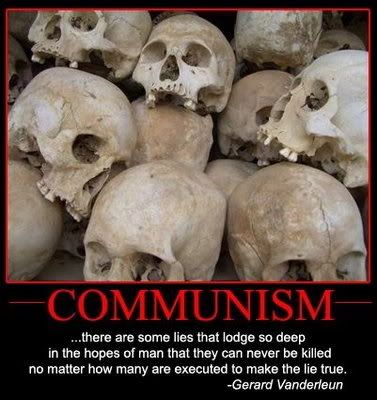

Time once again for this image:

And still, the lie is embraced by people who style themselves “Idealists without illusions.”