Remember to Honor the Others

I mentioned below that I had just finished reading Lt. Col. Dave Grossman’s On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society. This is a pretty sobering look at the actualities of lethal force, and I wanted to wait until Memorial Day for this post because Col. Grossman makes a point that I think the majority of our society doesn’t grasp. Doesn’t want to grasp, in fact. But I’ll get to that in a moment.

I was first introduced to the concepts explored by Col. Grossman in his book in an essay by Eric S. Raymond of Armed and Dangerous, The Myth of Man the Killer. Eric’s piece was about the reluctance of people to kill or even inflict injury until forced to by extraordinary circumstances, but also about the perpetuation of a belief in the “myth of man the killer” and what that belief has done to our society. If you haven’t read it, I strongly recommend you do.

But Col. Grossman, who has a bachelor’s degree in history, and a graduate degree in psychology, examines the aftermath of both inflicting and experiencing the exercise of lethal force – through the spectrum of the impersonal (bombing, shelling) to the up-close-and-personal of close-quarters combat.

While this book will be fodder for several future posts, this is the topic I want to explore on this Memorial Day.

Col. Grossman notes that during WWII studies have shown that only 15-20% of combat troops – the ones on the line facing the enemy with weapons in hand – “would take any part with their weapons” – that is, actually fire at the enemy. He notes, however, that the studies found

Those who would not fire did not run or hide (in many cases they were willing to risk great danger to rescue comrades, get ammunition, or run messages), but they simply would not fire their weapons at the enemy, even when faced with repeated waves of banzai charges.

I won’t get into the “why” of this in this essay, but accept it as fact, and understand that the military saw this as a major problem to be solved – not the “why,” but the “how to increase firing rates” question.

And they did. According to Grossman, changes in training regimens increased the firing rate during the Korean conflict to 55%. During the Vietnam war the firing rate was 95%. That number probably reflects conditions today in Afghanistan and Iraq. That rate explains why, after a 24-hour firefight in Mogadishu, Somalia without armor, without much air support, and without artillery support, US forces only 450 strong came out of that hostile city with only 18 dead, and 73 wounded. And inflicted around 1,000 Somali casualties. We have built an army of ferocious fighters, as Lt. Gen. William S. Wallace stated:

“The thing I remember most about the entire operation was the extraordinary endurance and bravery, heroism and sacrifice of the young Americans who were under my command.

“They were absolutely ferocious fighters when they needed to be,” Wallace recalled, “and in a moment they could turn into the most compassionate people you could ever imagine.”

That’s something we need to remember.

According to Col. Grossman, regardless of all the classic war movies you’ve seen, only about 2% of the people on the sharp end are capable of killing without suffering some psychological effect. The rest, even the ones who haven’t fired a shot in anger, are affected by the violence they’re exposed to. I, for example, cannot imagine the effect of being a direct witness to this:

or this on a daily basis:

An American soldier told me today that he has been telling kids to stay away from his unit so they won’t be killed. This is harder, on all parties, than it might seem to anyone who hasn’t seen first hand how much the kids here love the soldiers. The sound of heavily armored trucks rumbling through the streets has the same effect these kids as the tinkling bells of the “ice cream man” back home. Imagine having to tell kids to run the other way when they hear the icecream truck on a summer afternoon.

Recently, an insurgent hid behind a child in order to attack Americans. The tactic came as no surprise to the soldiers here. Terrorists routinely play wounded or feign their surrender in order to get close enough to launch an attack on Coalition or Iraqi Forces. In January I wrote about one bomber who grabbed the hand of a small child while she was playing on a sidewalk. Smiling, he walked with the child in hand, approaching some Iraqi police and exploded. Americans standing close by were unharmed.

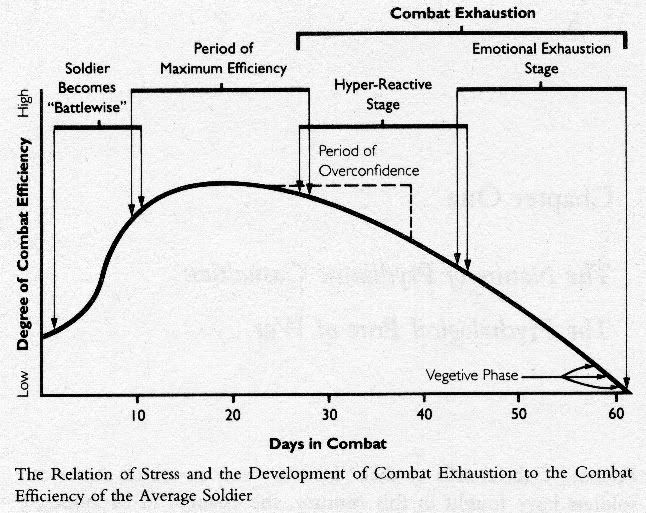

The ability to switch from ferocious fighter to compassionate person is an extremely admirable trait of our modern military, but one that would strain the emotional capacity of any human being to or even past the breaking point. There’s an interesting chart in Col. Grossman’s book, of what combat did to soldiers in WWII:

The effects of this are lessened, Col. Grossman notes, if the soldiers can be pulled “off the line” and given rest and recreation, but that wasn’t really possible during the Vietnam war, because there was no “line,” and VC activity could occur anywhere, any time. I’m not one to draw parallels between that war and this one, but in this one case the similarities are striking.

And in the Vietnam war, the psychological casualties were enormous.

Col. Grossman notes, however, that recovery from such psychological trauma is dependent on a number of factors. Grossman notes:

Something unique seems to have occurred in the rationalization process available to the Vietnam veteran. Compared with earlier American wars the Vietnam conflict appears to have reversed most of the processes traditionally used to facilitate the rationalization and acceptance of killing experiences. These traditional processes involve:

* Constant praise and assurance to the soldier from peers and superiors that he “did the right thing” (One of the most important physical manifestations of this affirmation is the awarding of medals and decorations.)

* The constant presence of mature, older comrades (that is, in their late twenties and thirties) who serve as role models and stabilizing personality factors in the combat environment

* A careful adherence to such codes and conventions of warfare by both sides (such as the Geneva conventions, first established in 1864), thereby limiting civilian casualties and atrocities

* Rear lines or clearly defined safe areas where the soldier can go to relax and depressurize during a combat tour

* The presence of close, trusted friends and confidants who have been present during training and are present throughout the combat experience

* A cooldown period as the soldier and his comrades sail or march back from the wars

* Knowledge of the ultimate victory of their side and of the gain and accomplishments made possible by their sacrifices

* Parades and monuments

* Reunions and contiued communication (via visits, mail, and so on) with the individuals whom the soldier bonded with in combat

* An unconditionally warm and admiring welcome by friends, family, communities, and society, constantly reassuring the soldier that the war and his personal acts were for a necessary, just, and righteous cause

* The proud display of medals.

We, the general public, can’t do much about the majority of these processes. We cannot make “safe zones” in Baghdad, we are not in control of troop rotation, we don’t award medals, but we are the ones in charge of that “unconditionally warm and admiring welcome.” It’s up to us to reassure the returning soldiers that we’re proud of them and what they’ve done.

What they’re witnessing and what they have to do as soldiers is destructive to the psyche of any human being. They are all in a crucible, under stresses most of us cannot imagine. So, by all means, respect the dead for their sacrifice this Memorial Day. But remember too the others who come back, both the wounded and the whole, who have answered our Nation’s call and put themselves on the sharp end. Honor them whenever you see them, and let them know that their sacrifices are appreciated. We’re doing a pretty good job, but not, I think, as a conscious process.

And we need to be.

Enjoy your Memorial Day. And thank a vet.

UPDATE: Just to give you a feel, read this post by Red2Alpha at This is Your War. A taste:

I pulled the trigger and a glittering brass cartridge spun out of the chamber and away. Half a heart beat later the shot roared back at me from the buildings lining Market St, coming back to me in waves as the detonation echoed up and down the street, off the flat surface of windows and walls, cars and people. It sounded deeper than a 5.56mm on a range, yet softer. My ears didn’t pop and ring.

The truck jerked slightly and lurched to a halt. I saw the figures in it start. The white paint on the plastic bumper was flaking off like a scab, revealing the yellow primer under neath. Dead bugs spattering the bumper with their black bodies. I smelled cordite.Since the IED things have been different for my team. We are more aggressive, quicker to anger. I’m angry all the time now. Everything and everyone is a threat to me. I’d much rather lash out with violence and rage than anything else.

Remember the role of the civilian at home. We do have one.