Let’s start out local.

Front page today, above the fold, in the local Daily rag newspaper:

One-third of freshmen found not ready for college courses

UA to teach high school level math in the fall

Let us fisk:

The University of Arizona will teach high school level math starting in the next school year, because a third of its freshmen aren’t ready for college level math, officials said.

Really? A third?

Back when I wrote The George Orwell Daycare Center a report had been released indicating that:

30% of students in the Tucson school districts fail basic subjects, but 90% are promoted to the next grade anyway. Plus, investigation suggests that up to a quarter of the students receiving passing grades should not be. (For the innumerate out there, that’s possibly over half, in total.) Nor is this limited to the Southwest.

The AP reports:

More than 50 percent of students at four-year schools and more than 75 percent at two-year colleges lacked the skills to perform complex literacy tasks.

That means they could not interpret a table about exercise and blood pressure, understand the arguments of newspaper editorials, compare credit card offers with different interest rates and annual fees or summarize results of a survey about parental involvement in school.

This would seen to lend further credence to those reports.

I wonder how long the U of A has been teaching remedial English?

The class will cover intermediate algebra through a lecture component, an online component and required time with trained peer instructors.

“It’s math that you would hope students already knew coming in, and a lot of them don’t,” said William McCallum, the UA’s math department head.

About a third of the UA’s 7,000 freshmen didn’t place in college math in a placement test they take during class registration time.

“We don’t want to put students into classes that they’re going to fail,” McCallum said.

Two-thirds of freshmen were ready to take college algebra, which is required for most degree programs, or “math in modern society,” a class for students whose fine arts or humanities degree programs don’t require much math.

I would love to get my hands on a copy of the final exam for “math in modern society.”

Those who take the new high school level math class – about 1,000 students per year at full capacity – also will get help with adjusting to the university culture, finding out what it’s like to take a college math class and learning which study skills are required for success.

That they SHOULD have learned before GRADUATING FROM HIGH SCHOOL.

The class doesn’t satisfy the UA’s math requirements; it just gets students ready for college algebra or “math in modern society.” The class will count as a general elective toward a degree.

Most UA students who aren’t ready for college math take intermediate algebra through Pima Community College and transfer the credit to the UA. PCC faculty taught seven sections of the class at the UA campus in the fall.

But if a student takes the class through PCC, it doesn’t count as part of the student’s full-time schedule needed to get financial aid. So students end up taking five classes at the UA plus the math class at Pima. Those underprepared and overloaded students are less likely to succeed as freshmen.

Then perhaps they should prepare before becoming freshmen?

“The main reason we’re doing this is to retain those students,” Vice Provost Gail Burd said.

Yes, you desperately need their tuition dollars.

The UA also will benefit from the tuition revenue that would otherwise go to the community college.

The university has an open admissions policy and is working on the state’s goal of producing more degree holders.

Said degrees which are becoming almost as worthless as a High School Diploma. But that’s what happens when something becomes an entitlement – its value declines, sometimes precipitously.

“My attitude is: If we admit students who are not sufficiently prepared in mathematics, we have some sort of obligation to help them,” McCallum said.

Perhaps then you shouldn’t admit them??

The UA’s undergraduate council came to the same conclusion, said Jake Harwood, a UA communication professor and the council chair.

Color me shocked.

The council, composed of faculty members and others who make curriculum decisions, at first was concerned about starting down a slippery slope of teaching remedial classes, but the faculty has to work with the students it gets, Harwood said. So the council approved the class.

Because otherwise the University might have to get smaller, and who would THAT benefit?

“If we’re admitting you, we’re saying you’re ready for college,” Harwood said. But if students aren’t ready, especially in a fundamental area such as quantitative skills, the UA should help them instead of telling them to sink or swim, he said.

How about “If you’re not ready, we’re not ADMITTING YOU”?

Doesn’t anybody in administration do logic anymore, much less math?

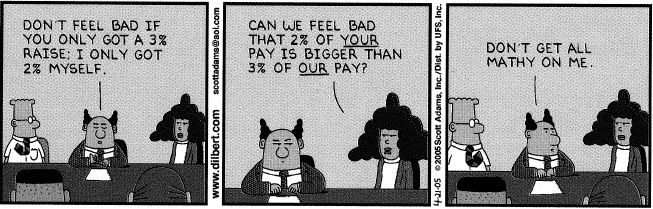

I thought this was an appropriate place to put that.

Next up: The Standford School of Education!

Over the weekend, both in email and in a comment, Unix-Jedi sent me links to a heartwarming story:

A Model School Flops

It sounded like a great idea: Stanford education professors would create a model school to show how to educate low-income Hispanic and black students.

Or, as it’s turned out, how not to.

In March, Stanford New Schools (aka East Palo Alto Academy) — a charter high school started in 2001 and elementary grades added in 2006 – made California’s list of schools in the lowest-achieving five percent in the state.

This month, the Ravenswood school board denied a new five-year charter. The elementary school — now with K-4 and eighth grade — will close in June. Another year or two wouldn’t be enough to improve poor student performance and weak behavior management, Superintendent Maria De La Vega told the board.

The high school will get two years to find a new sponsor: the local high school district has said “no,” but there are other options.

How did it happen? Stanford New Schools, run by the university’s school of education, seems to stress social and emotional support over academics.

Stanford New Schools hires well-trained teachers who use state-of-the-art progressive teaching methods; Stanford’s student teachers provide extra help. With an extra $3,000 per student raised privately, students enjoy small classes, mentoring, counseling and tutoring, technology access, field trips, summer enrichment, health van visits, community college classes on campus, and community service opportunities. The goal is to send graduates to college as critical thinkers, lifelong learners, and “global citizens.”

“Global Citizens” who are illiterate and innumerate, have no knowledge of history or civics or science, but by God they have a HIGH SCHOOL DIPLOMA and they FEEL GOOD about themselves!

The school provides students a web of support, reports the New York Times:

High school students have one teacher/adviser who checks that homework is done, and when it is not, the teacher calls home. Teachers know students’ families and help with issues as varied as buying a bagel before an exam to helping an evicted family find a home. Teachers stay late and work weekends, and tend to burn out quickly — causing a high rate of turnover.

EPA Academy enrolls very disadvantaged students: Most are the children of poor and poorly educated Spanish-speaking immigrant families; the rest are black or Pacific Islanders. Their English skills are poor. Those who come in ninth grade are years behind in reading and math.

In comments on the news stories that have run, I see a common refrain: It’s impossible to teach these kids. Not even Stanford can do it.

Ahem. Time once again for Den Beste’s Definition of Cognitive Dissonance:

When someone tries to use a strategy which is dictated by their ideology, and that strategy doesn’t seem to work, then they are caught in something of a cognitive bind. If they acknowledge the failure of the strategy, then they would be forced to question their ideology. If questioning the ideology is unthinkable, then the only possible conclusion is that the strategy failed because it wasn’t executed sufficiently well. They respond by turning up the power, rather than by considering alternatives. (This is sometimes referred to as “escalation of failure”.)

But no, no! says Ms. Jacobs:

But other schools with demographically identical students are doing much better. The top-scoring school in the district is East Palo Alto Charter School (EPAC), a K-8 run by Aspire Public Schools, Stanford’s original partner. An all-minority school, EPAC outperforms the state average.

Rather than send EPAC graduates to Stanford’s high school, Aspire started its own high school, Phoenix, which outperforms the state average for all high schools. All students in the first 12th grade class have applied to four-year colleges.

All of them. And I’m willing to bet that 30% aren’t going to have to take high-school level algebra, either.

But wait! It gets better!

Aspire co-founded East Palo Alto Academy High with Stanford, but bowed out five years ago. There was a culture clash, Aspire’s founder, Don Shalvey told the New York Times. Aspire focused “primarily and almost exclusively on academics,” while Stanford focused on academics and students’ emotional and social lives, he said.

Okay, boys and girls, say it along with me! “Which philosophy WORKS?!?“

But Cognitive Dissonance is still in effect:

Deborah Stipek, Stanford’s dean of education, says the elementary school is too new — in its fourth year, but with only two years of scores — to be judged. Stanford considers the high school a success.

In an email to Alexander Russo, Professor Linda Darling-Hammond, who helped create the high school, defended the high school’s “strong, highly personalized college-going program.” The graduation rate of 86 percent exceeds the state average. “In addition, 96 percent of graduates are admitted to college (including 53 percent to four-year colleges) — twice the rate of African American and Latino students in the state as a whole.” Half the students enroll in Early College classes on campus.

Given the horrendous drop-out rate for Ravenswood students who go to large public high schools — it’s estimated only one out of three receives a diploma — EPA Academy is helping students stay in school.

But its graduates are not prepared for college.

I won’t rain on Ms. Jacob’s follow up, but I want to interject here: Fifty-three percent of East Palo Alto Academy High’s students get admitted to a four-year school (and we’ve seen what the requirements for that have declined to), but ALL of the graduating class of Aspire’s Phoenix high school have applied to four-year colleges.

Same student demographics, massive disparity in philosophy, and massive disparity in outcome.

Ms. Jacobs:

The 96 percent college admission rate is meaningless, since it includes community colleges, which take anyone, and California State University campuses, which admit students with a B average or better, regardless of test scores.

EPA Academy students are graded on a five-dimensional rubric, based on (1) Personal Responsibility; (2) Social Responsibility; (3) Communication Skills; (4) Application of Knowledge; and (5) Critical and Creative Thinking.

Only 20 percent of the grade is based on knowledge, notes Michele Kerr, who taught an ACT prep course for disadvantaged students at a nonprofit from 2007-09. Compared to district high school students, East Palo Academy tutees had “the lowest skills and the highest grades,” Kerr recalls. Students with high A averages turned out to have very poor reading and math skills, though their writing was relatively strong.

Lowest skills, highest grades.

Yup, that’s modern teaching!

EPA Academy students got into CSU on their grades, while much stronger students with lower grades were shut out, says Kerr, now a Stanford-trained high school teacher.

On CSU’s test of college readiness, no EPA Academy 11th graders were deemed ready for college English; only 11 percent were deemed ready for college-level math. Of course, they might catch up in 12th grade. But the state exam shows 11th graders are far behind. In English Language Arts, 54 percent are below basic, 40 percent basic, and only 6 percent proficient. No students tested as proficient in Algebra II or chemistry, 9 percent in biology, and 6 percent in U.S. history.

They’re in school five days a week, supposedly taking six hours of class per day. WHAT THE HELL ARE THEY BEING TAUGHT?

The median scores for SAT takers are in the high 300s in each section, about the 15th percentile. ACT scores average 15, equally low.

Apparently nothing that anybody tests for.

And we return to Sowell’s Social Visions once again. Had anybody asked me back when Stanford New Schools started their experiment, I’d have predicted precisely this outcome. I wouldn’t have understood as well as I do now why it would have been the right prediction, but I’d have made it: Total Failure.

The Unconstrained (“Progressive”) vision doesn’t work. But that vision embraces cognitive dissonance and hangs on for dear life in the face of all the evidence. Jacobs concludes:

When I started the reporting that led to my charter school book, Our School, I planned to write about the Aspire-Stanford school. I was at the school board meeting when Aspire-Stanford got the charter. I talked to East Palo Alto parents eager for a high school in their own town. I interviewed Shalvey and Darling-Hammond, who took the lead in getting the high school started.

However, I couldn’t get the access I needed — the inexperienced teachers didn’t want a writer taking note of their mistakes — so I ended up at Downtown College Prep, a charter high school in San Jose designed for underachievers from Mexican immigrant families.

As at East Palo Alto Academy, DCP started with a progressive philosophy and very high ideals. But the two high school teachers who started the school had no trouble acknowledging mistakes. When things didn’t go as they’d hoped — which happened a lot — they tried something else. No time or energy was wasted blaming the students’ poverty or the tests. The unofficial motto was: We’re not good now but we can get better. And they did.

Will Stanford education professors learn from their mistakes? I fear they’ll write off the elementary, claiming the program didn’t get enough time, and continue to claim the high school as a success. That would be a waste of a “teachable moment.”

Pointy-headed professors of Education admit error?

Inconceivable!

I will reiterate my ongoing argument:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aCbfMkh940Q&hl=en_US&fs=1&rel=0&w=640&h=385]