November 12, 1969. The Apollo 12 mission launched that morning. As the rocket cleared the launch tower, responsibility for the mission transferred from Launch Control in Cape Canaveral to Mission Control in Houston. Thirty-four seconds into the launch, the rocket was struck by lightning. Suddenly all the instruments on the capsule control panel went crazy. Ground telemetry was garbled. It was struck again at 52 seconds, and every alarm light on the console was flashing. The rocket maintained its launch path but no one in the capsule or on the ground other than the ground based radar could tell what was going on.

If instrumentation and telemetry could not be restored, the launch would have to be aborted.

The astronauts and ground controllers scrambled to understand what had happened. The engineer on the EECOM station that morning was John W. Aaron, and it was his job to be intimately familiar with the power systems of the command and service modules of the Apollo craft. In previous simulations he had seen something similar. He quickly called out: “CAPCOM, EECOM – Try SCE to AUX,” telling the Capsule communicator, the man whose job it was to handle all communication between the spacecraft and mission control, to tell the pilot to flip a switch. No one else in the room knew what that switch was.

“FCE to AUX?”

“No, S, SCE to AUX.”

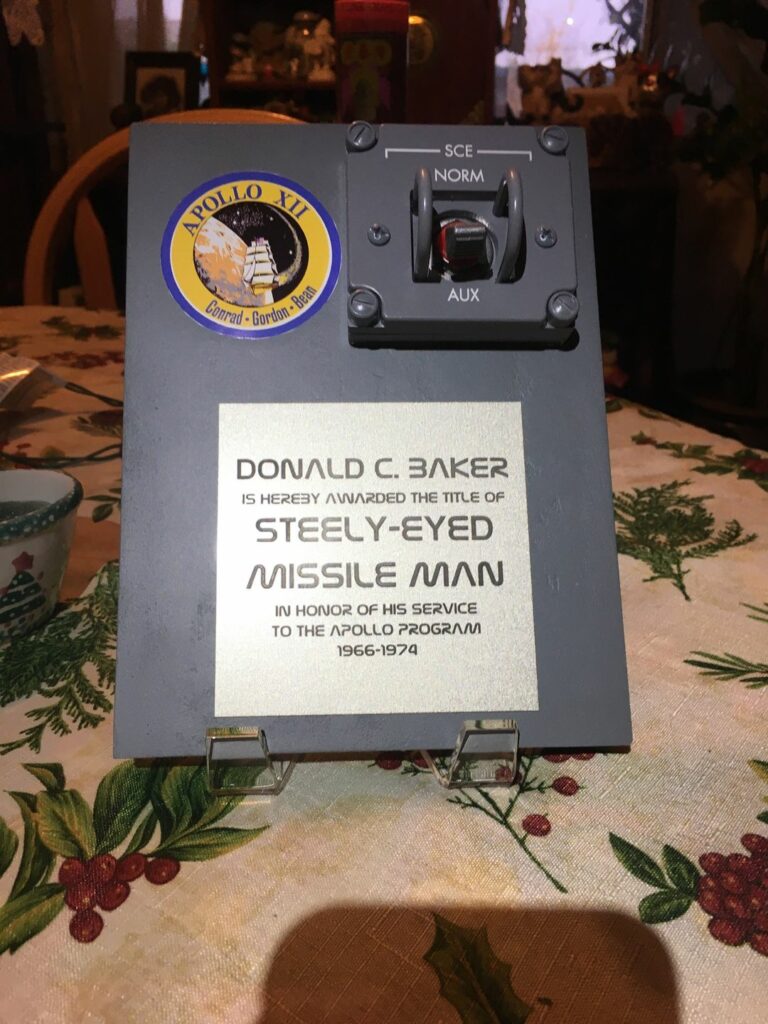

The recommendation was relayed to Apollo 12 thirty-six seconds after they lost their instruments. Neither Commander Pete Conrad nor Command Module Pilot Richard Gordon recognized the reference to “SCE,” but Lunar Module pilot Alan Bean did, and knew where the switch was. SCE stood for Signal Conditioning Electronics, the electronics that converted all the signals from the various sensors and equipment to voltages or currents that could be easily displayed or transmitted to the ground, and John Aaron had told them to switch their power supply to the auxiliary power source. Alan Bean found and flipped the switch, and all the instruments and ground telemetry came back to life.

There were still many minutes of resetting circuit breakers and clearing faults, but the mission was saved. For his knowledge, quick thinking and grace under pressure, John W. Aaron was named a Steely-Eyed Missile Man that day.

The rocket stayed on course even after the lightning strikes because the guidance computer, located in the body of the Saturn V, stayed functional. My father worked on the Instrument Unit – the Saturn V guidance system – for IBM at Cape Canaveral. This Christmas I gave him this: