A Thousand Times, NO!.

More Supreme Courtage, lost in the news of today’s Ten Comandment and Grokster decisions. Thanks to Mike of Feces Flinging Monkey for the heads-up.

Today the Court decided Town of Castle Rock v. Gonzales just as I said it would back in November: The government is NOT responsible for your protection.

The background info, from the earlier piece:

(O)ne Jessica Gonzales has sued the town of Castle Rock for failing to enforce a protective order against her estranged husband, who abducted their three children, murdered them, and then committed suicide by cop. Ms. Gonzales sued because, she says, her husband violated the restraining order by abducting the children, and the City of Castle Rock police department made no effort to recover her children after she repeatedly asked them to enforce the restraining order. She sued under a due-process argument, claiming that the failure of the police to act violated her rights. Essentially, she argued that by obtaining the restraining order she had a “special relationship” that meant that either: A) the police were obligated to enforce the order; or B) the police were obligated to tell her that they would not.

I’ve written several posts on the failure of restraining orders to restrain anybody not willing to be restrained. Zendo Deb of TFS Magnum has made restraining order failures one of her specialties. The court ruled, 7-2, in a decision written by Scalia that Mrs. Gonzales’s novel 14th Amendment Due Process argument failed because:

Respondent did not, for Due Process Clause purposes, have a property interest in police enforcement of the restraining order against her husband.

Scalia goes on some 20 pages to make the purely legal point, concluding:

Although the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment and the Civil Rights Act of 1871, 17 Stat. 13 (the original source of §1983), did not create a system by which police departments are generally held financially accountable for crimes that better policing might have prevented, the people of Colorado are free to craft such a system under state law.

Ah, once again SCOTUS secures State’s Rights.

Justice Stevens’ dissent is an interesting echo of a much earlier case I’ve referred to before. Here’s part of what Stevens (joined by Ginsberg) had to say:

Respondent certainly could have entered into a contract with a private security firm, obligating the firm to provide protection to respondent’s family; respondent’s interest in such a contract would unquestionably constitute “property” within the meaning of the Due Process Clause. If a Colorado statute enacted for her benefit, or a valid order entered by a Colorado judge, created the functional equivalent of such a private contract by granting respondent an entitlement to mandatory individual protection by the local police force, that state-created right would also qualify as “property” entitled to constitutional protection.

Compare that with the NY Court of Appeals dissent in Riss v. New York from 1968:

Linda Riss, an attractive young woman, was for more than six months terrorized by a rejected suitor well known to the courts of this State, one Burton Pugach. This miscreant, masquerading as a respectable attorney, repeatedly threatened to have Linda killed or maimed if she did not yield to him: “If I can’t have you, no one else will have you, and when I get through with you, no one else will want you”. In fear for her life, she went to those charged by law with the duty of preserving and safeguarding the lives of the citizens and residents of this State. Linda’s repeated and almost pathetic pleas for aid were received with little more than indifference. Whatever help she was given was not commensurate with the identifiable danger. On June 14, 1959 Linda became engaged to another man. At a party held to celebrate the event, she received a phone call warning her that it was her “last chance”. Completely distraught, she called the police, begging for help, but was refused. The next day Pugach carried out his dire threats in the very manner he had foretold by having a hired thug throw lye in Linda’s face. Linda was blinded in one eye, lost a good portion of her vision in the other, and her face was permanently scarred. After the assault the authorities concluded that there was some basis for Linda’s fears, and for the next three and one-half years, she was given around-the-clock protection.

Linda has turned to the courts of this State for redress, asking that the city be held liable in damages for its negligent failure to protect her from harm. With compelling logic, she can point out that, if a stranger, who had absolutely no obligation to aid her, had offered her assistance, and thereafter Burton Pugach was able to injure her as a result of the negligence of the volunteer, the courts would certainly require him to pay damages. (Restatement, 2d, Torts, § 323.) Why then should the city, whose duties are imposed by law and include the prevention of crime (New York City Charter, § 435) and, consequently, extend far beyond that of the Good Samaritan, not be responsible? If a private detective acts carelessly, no one would deny that a jury could find such conduct unacceptable. Why then is the city not required to live up to at least the same minimal standards of professional competence which would be demanded of a private detective?

Pretty much the same language, 37 years later – with the same result. The State cannot, (or at least will not) be made financially accountable for failure to protect, because if it were liable, it would be bankrupted by lawsuits in short order. The goverment is not responsible for your protection because it’s not possible for it to protect everyone, all the time.

Something which Mrs. Gonzales found out in a brutal and shocking fashion, and has now had her face rubbed in it.

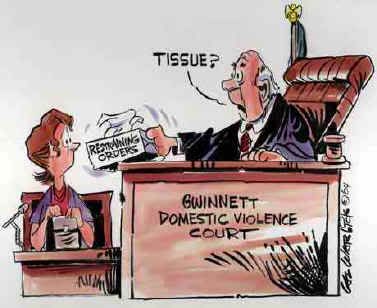

Once again, it’s time for that cartoon:

Think about that the next time you need to dial 911.

If you have the time.

Blake at Nashville Files has something to say, too.

UPDATE: The WaPo reports:

Groups Back Restraining Orders Amid Ruling

By JON SARCHE

The Associated Press

Tuesday, June 28, 2005; 9:15 AMDENVER — Victims’ advocates scrambled to reassure the public that restraining orders are still effective for preventing domestic violence, despite a U.S. Supreme Court ruling that police cannot be sued over the way they enforce them.

The 7-2 ruling Monday ended a lawsuit by a Colorado woman who claimed Castle Rock police did not do enough to prevent her estranged husband from killing their three young daughters. The ruling said Jessica Gonzales did not have a constitutional right to police enforcement of the court order against her husband.

“The second tragedy in this case could very well be that victims of domestic violence will read this opinion to mean that protection orders are not worth the paper they’re printed on, and that impression would be false,” said Richard Smith, a Washington lawyer who filed a brief in support of Gonzales.

Might that be because, in some cases, protection orders aren’t worth the paper they’re printed on? Because, as Volusia County Sheriff Ben Johnson put it plainly, “An injunction is fine for someone who is willing to accept the rules… When someone is bound and determined they are going to do a criminal act, it is hard to stop it.”

Trish Thibodo, executive director of the Colorado Coalition Against Domestic Violence, said police still have a responsibility to enforce restraining orders and to take them seriously.

But the Court (and every other court so asked) has said they don’t have that responsibility.

“Nothing’s changed,” she said.

Precisely.

City governments feared that a ruling in Gonzales’ favor could open them to a flood of lawsuits. Judges in Colorado issued more than 14,000 restraining orders in fiscal 2004.

“The potential for liability was just completely out of this world,” said Brad Bailey, an assistant city attorney in Littleton who filed a brief in support of the Castle Rock police department.

That’s exactly it. It’s a question of fiscal liability. A private business can be held responsible, but the State CANNOT.

Gonzales’ attorney, Brian Reichel, did not immediately return a call seeking comment.

On ABC’s “Good Morning America,” Gonzales said now that the Supreme Court has ruled, she is moving on.

“I’m going to continue my advocacy for other victims,” she said. “I believe that there is a lot to be done, and this is a new beginning for me. And continuing to try to find some resolution for why my three children were murdered.”

Because your estranged husband was a wacko.

Gonzales sued the Castle Rock police department, claiming officers ignored her pleas to find her husband after he took the three girls, ages 10, 9 and 7, from the front yard of her home in June 1999 in violation of a restraining order. Hours later, Simon Gonzales died in a gunfight with officers outside a police station. The bodies of the girls were in his truck.

Gonzales argued that she was entitled to sue based on her rights under the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and under a Colorado law that says officers must use “every reasonable means” to enforce a restraining order.

She contended that her restraining order should be considered property under the 14th Amendment and that it was taken from her without due process when police failed to enforce it.

A federal judge in Denver dismissed her lawsuit, but the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals revived it, saying the restraining order was a government benefit that should be treated like any other property.

But Justice Antonin Scalia, writing for the high court’s majority, said Colorado’s law does not entitle people who receive protective orders to police enforcement.

Smith, Gonzales’ attorney, called the ruling “an open invitation to states to look at their statutes and enhance them and to provide the kind of protections that victims need.”

He said lawmakers should ensure that police departments can be sued in state courts for failure to enforce protective orders. Under current state law, governments in Colorado and other states are immune from such lawsuits, forcing Gonzales to turn to the federal courts.

“The ultimate conclusion in this case is that states need to stand up and become accountable in protecting the innocent victims of domestic violence,” Smith said.

They never will, because if they do then shortly after they will become liable for not protecting victims of non-domestic criminal violence, and then non-violent crime.

Castle Rock officials contend they tried to help Gonzales. Police twice went to the estranged husband’s apartment, kept an eye out for his truck and called his cellular phone and home phone.

Gonzales reached him on his cell phone, and he told her that he had taken the girls to an amusement park in nearby Denver. Gonzales maintains that police should have gone to the amusement park or contacted Denver police.

“We all still feel really bad about this whole situation, but in response to the allegations we were unresponsive and so on, these were all totally not true,” said Police Chief Tony Lane, who was chief at the time of the slayings.

The Washington, D.C. police department was unresponsive in the Warren case, and the NYPD was completely unresponsive in the Riss case, and they were cleared of any liability. This is absolutely no different.

“The deaths of these girls, while tragic, I think the learning experience we gained from this will help us deal better with these situations in the future,” he said.

Or not. From a legal standpoint, it doesn’t matter a damn.

(H/t to Mike, again.)